June 11, 2024

How Does Cycling Infrastructure in These Global Cities Measure Up?

In 2021, ITDP launched the Cycling Cities campaign, building off of the global momentum around cycling that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, many cities swiftly responded to changing mobility needs by setting up temporary cycle lanes, designating reduced-traffic streets, and facilitating access to bicycles through reduced-fare or free bikeshare programs. In the years since, Cycling Cities cohort cities have committed to more ambitious plans to support cycling, which include everything from infrastructure to policies to local campaigns.

As discussed in the first part of this blog series, ITDP’s People Near Protected Bikelanes (PNB) indicator is a helpful metric to track an individual city’s progress providing accessible cycle infrastructure for people, and to compare across cities. In this article, we’ll take a deeper look at four Cycling Cities cohort cities — Bogotá, Colombia; Glasgow, Scotland; Santiago, Chile; and Los Angeles, USA — and the stories that each city’s PNB can tell us about urban cycling.

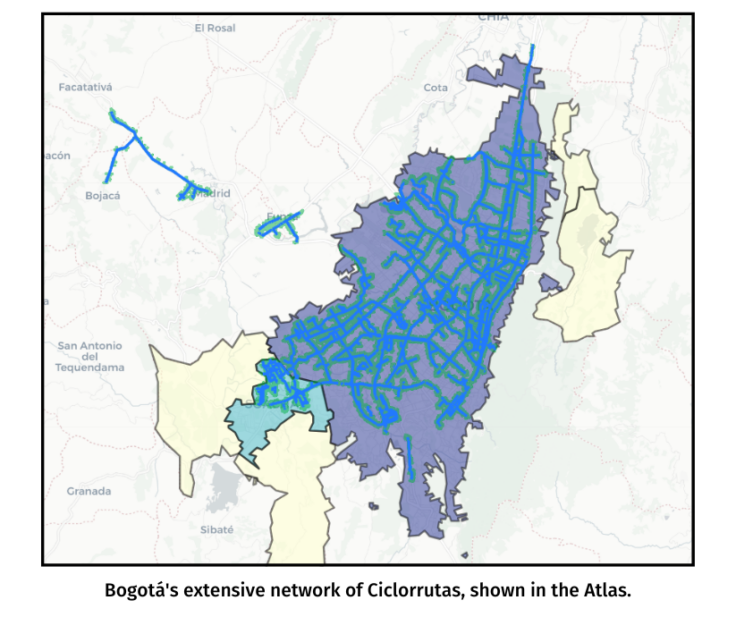

Bogotá, Colombia

In Bogotá, 51% of residents live near protected bikeways — a 10% increase since 2021 and the highest ranked Global South city for this indicator. For decades, Bogotá has consistently invested in cycling as a transport mode, allocating space on streets for cycle lanes and opening streets to people on bicycles and on foot every Sunday during Ciclovia. In 1998, construction began on a network of safe bicycle routes known as the Red de Ciclorrutas. Initially integrated into pedestrian sidewalks, the project started with just eight kilometers of bike lanes. Over the years, Bogotá has significantly expanded its cycling infrastructure and improved the quality of lanes, developing one of the world’s most extensive protected cycle lane networks totaling over 540 kilometers.

The city’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic also included the creation of 84 kilometers of temporary bike lanes, 28 kilometers of which were made permanent. Meanwhile, expansion of the Cicloruta network has greatly enhanced accessibility for cyclists, connecting residential neighborhoods, commercial districts, and key urban hubs. This connectivity has transformed cycling into a viable mode of transportation for daily commutes, errands, and leisure activities, significantly impacting the lives of Bogotá’s residents. Upwards of 7% of trips in Bogotá are now made by bicycle, or approximately 650,000 trips per day.

Glasgow, Scotland

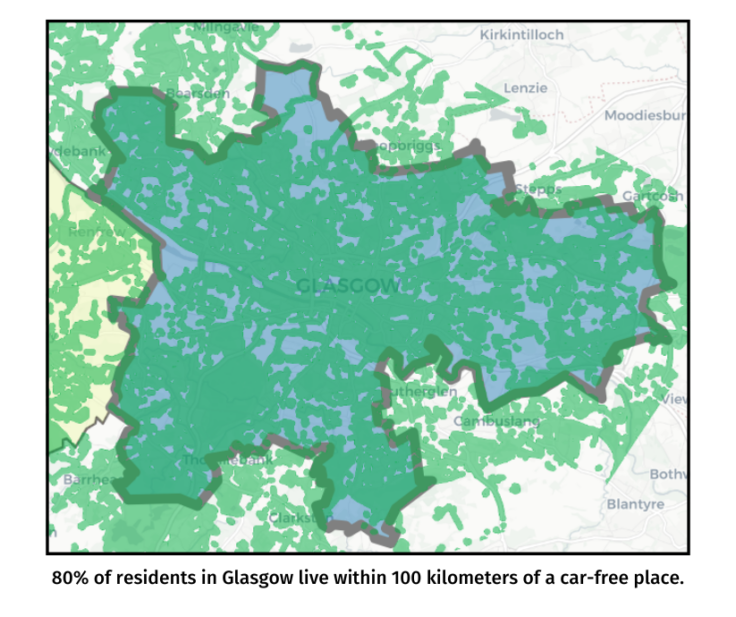

Glasgow’s Strategic Plan for Cycling aims to make the city accessible, safe, and attractive for all cyclists. This includes a target to expand the city’s cycle network to 400 kilometers by 2025 and eventually to 590 kilometers. As of 2024, Glasgow has 228 kilometers of bikeways, of which 170 are physically protected, yielding a 31% PNB. Implemented in phases over the past several years, Glasgow’s City Ways program is one way the city has significantly expanded accessibility and safety for cyclists.

For example, South City Way, connects the city center with communities in the south of Glasgow along Victoria Road. This project also includes upgraded intersections and improved signage along the cycle lane, providing a safe and convenient cycling corridor that connects key destinations such as universities, business districts, and residential areas. The South City Way project, which cost approximately £6.5 million, was funded through the Scottish Government’s Community Links Plus program with matching funds from the City Council.

Glasgow is enhancing the convenience of active transportation, not just by expanding its cycle network, but by pursuing projects like Spaces for People. Implemented during the pandemic, the Spaces for People program deployed car-free school zones, pop-up bike lanes, parks and open spaces, neighborhood traffic calming, and other projects. While initially temporary, many of these interventions have been made permanent. Glasgow ranks very highly on another Atlas indicator, People Near Car-Free Places, with 80% of people living within 100 kilometers of a car-free park, plaza, street, or other space.

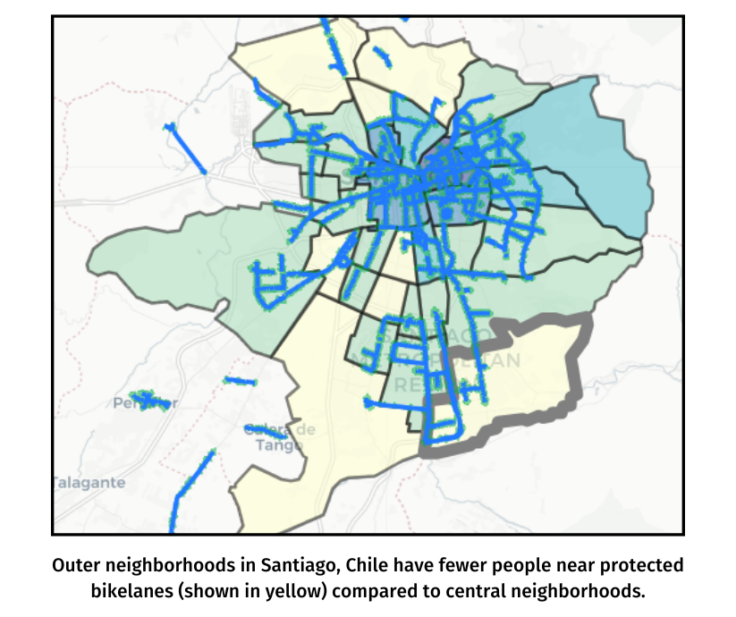

Santiago, Chile

Santiago, with 26% of its residents near protected bikeways, embarked on its cycling journey in 2006. At that time, the city committed to building 1,000 kilometers of bike lanes and supported education programs, road space redistribution, and the BikeSantiago bikeshare and BMov Trici bike taxi programs. The city’s story illustrates how a comprehensive approach, combining policy changes, education, and infrastructure development, can transform urban mobility. At the commune level, the distribution of bike lanes is uneven however. People living in central neighborhoods like Santiago, Providencia, and Independencia have high access to protected bike lanes, 73%, 89%, and 62% respectively — much higher than at the municipal level.

Peripheral regions such as Puente Alto and San Bernardo in the South have significantly lower access at 17% and 3% respectively. These outer neighborhoods have high mode shares of bicycle trips for work purposes, as revealed by origin and destination survey data, and could benefit from additional infrastructure to better support these trips. In this case, People Near Protected Bikelanes helps to identify gaps in the network and potential areas for improvement, such as improving connections between these peripheral neighborhoods and the city center.

Los Angeles, USA

Though mostly flat and with mild, dry weather year round, Los Angeles is not well-known for cycling. The sprawling metropolis is instead nearly synonymous with traffic, ranking in the top ten most congested cities in the US year over year. However, the city’s urban planning initiatives, such as the Mobility Plan 2035 and Vision Zero LA, prioritize cycling as a sustainable mode of transportation. Focused on enhancing cycling infrastructure within the urban core, these plans aim to improve connectivity and safety by installing protected bikelanes. The Atlas shows that 6% of people in the municipality of Los Angeles (about 234,000) live near protected bikelanes, of which there are approximately 136 miles (219 kilometers).

The city’s expansive size, existing road infrastructure, and historical prioritization of car travel pose challenges to creating a cohesive and extensive cycling network. Additionally, the uneven distribution of cycling infrastructure investments and varying levels of community support for cycling initiatives have slowed implementation. Comparatively, in nearby municipalities of Irvine, Alondra Park, Grand Terrace, and San Juan Capistrano, PNB exceeds 20%. Irvine’s PNB of 50% (roughly 156,000 people) is likely influenced by the presence of the University of California, Irvine and the city’s urban planning principles favoring mixed-use development and pedestrian-friendly design, as outlined in its Sustainable Mobility Plan. To transform cycling in a city like Los Angeles, a concerted policy and community campaign is needed to create safer, accessible streets for all residents.

From these examples, it is clear that cities can provide protected cycling infrastructure that is accessible and inclusive of the needs of their residents. However, total kilometers of cycle lanes may not tell the full story. PNB offers cities an opportunity to evaluate existing conditions and prioritize investments to build out their cycle networks based on such data. Decision-makers should take gaps in their local network or untapped demand (in densely populated, low-infrastructure neighborhoods) into account, and then track how new cycle infrastructure impacts PNB. By implementing comprehensive and well-connected networks of bikelanes, cycling becomes a more appealing mode of transport to everyone, especially when integrated with public transit options.

The future of the cycling cities needs to include considerations for indicators like PNB that — when balanced with other sustainable mobility decision — can ensure that urban infrastructure actually works for communities.