September 04, 2025

Global Cities Can Still Turn the Tide on Car-Centric Growth

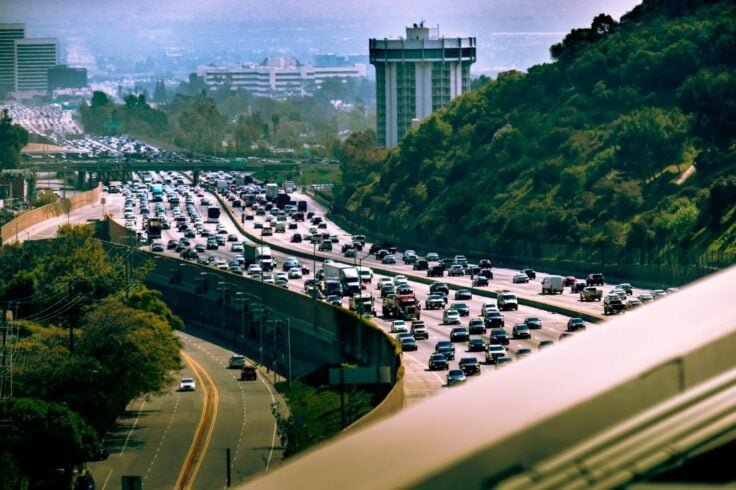

A key objective of sustainable transport policy is to reduce driving in cities, which is often measured by vehicle kilometers traveled (VKT).

Policies that reduce VKT have a number of health, economic, and climate benefits for cities.

Facilitating a shift away from private vehicles may seem challenging in cities experiencing rapid growth, especially as data in nearly all of the key regions where ITDP operates indicate a rising trend in VKT. This is expected to further increase by 50% globally through 2030, or approximately 15% every five years since 2015. In the Africa region, VKT by private passenger vehicles is expected to more than double between 2015 and 2030, which amounts to about 26% every five years.

While this may seem a daunting challenge, there is also evidence that ambitious VKT reductions are still achievable, without limiting economic growth, if cities and policymakers take decisive actions and make investments now to mitigate car-oriented growth. Real-world examples from a number of regions already exist – and they demonstrate that consistent, comprehensive interventions can significantly alter people’s mobility choices in favor of more sustainable options.

Learn more about policies that can help cities to reduce vehicle use in ITDP’s Taming Traffic report.

Sustainable mobility measures – such as transit-oriented development, road pricing, and improvements to walking and cycling infrastructure – are key to reducing unnecessary vehicle trips. Restrictions on car use in urban cores with low- and zero-emission zone strategies have successfully curtailed private vehicle demand and shifted travel behavior at scale, while continuing to provide reliable access to destinations. Such cases suggest that a key barrier to progress is not technical feasibility, but rather a need for stronger commitments from the public and private sectors into rethinking urban development.

Another Model Is Possible

At a high level, ITDP’s Compact Cities Scenario-Electrified research has provided strong evidence that a shift away from urban passenger vehicles towards walking, cycling, and electric public transit is not only better for the environment, but is also significantly less expensive for both governments and individuals. There are tangible examples of cities reducing VKT over relatively short timeframes using these types of policy approaches.

In the city of Seattle, USA, for instance, local commitments to walking, cycling, and transit infrastructure have led to the VKT per capita decreasing by 13.5% between 2005 to 2012. In Paris, VKT decreased by 16.5% over three years, largely due to heavy investment in cycling networks and public space upgrades in recent years. Paris received the 2023 Sustainable Transport Award for its targeted efforts to improve cycling infrastructure and transit integration – notable directing millions of Euros into these projects.

At a national level, such transformation is also possible, primarily through decoupling the notions of economic growth and access to jobs from car ownership. In the 1970s, the United Kingdom had some of the highest rates of car usage and VKT in the world. Over the last few decades however, while the U.K.’s trend still continues to inch upwards, the country’s economy has continued to expand rapidly while limiting per capita VKT growth to a more modest 8.5% (1974-2023) by reducing highway expansions, promoting public transit, and focusing on traffic demand strategies.

Other countries managed to avoid massive VKT growth in the first place by decoupling its growth model from car use much earlier. In 1970, for instance, countries like Japan, the Netherlands, and South Korea all had levels of VKT per capita that were previously on track to achieve levels we now see in the U.S., as car manufacturing and global trade surged in the post-war years. However, a strategic package of mobility policies has helped shift the direction of those countries, moving them towards becoming global models for sustainable, efficient, and innovative urban mobility.

Why is parking reform vital to reducing VKT in cities? Learn more here.

If these nations had followed the U.S.’ car-driven development model, the average person in these regions would be driving nearly 20,000 kilometers per year. Instead, they average only 7,000 kilometers based in 2022 estimates. And these nations’ economies have continued to grow despite their low-VKT model. Japan managed to reduce its VKT/capita from 2018 to 2023 by 6% while continuing to grow its economy. Key contributors to this fall in VKT include Tokyo’s rail-focused design which emphasize dense, mixed-use development, well-connected public transit, high fuel taxes, and parking reforms.

Collectively, all of these efforts have reduced Japan’s per-capita driving to 45% below U.S.-model predictions (2022). Similarly, the Netherlands stabilized VKT per capita through its cycling infrastructure commitments and low-emission zones policy approaches. South Korea is also accelerating toward more compact urban design and planning with a focus on walkable neighborhoods with a mix of housing, commercial, and public spaces. Thus, car dependency and high VKT are not inevitable outcomes of economic growth, but rather direct policy choices that can have lasting impacts on people’s everyday mobility. And, in places like the U.S., the negative outcomes of these choices are not easily undone.

Prioritizing transit and compact land use to support short trips by bike or by foot, and pricing driving behaviors to reduce unnecessary trips, can all help unlock more sustainable and equitable mobility. It is important to note that many examples of countries that are achieving VKT reductions are categorized as high-income and have also experienced relatively low rates of population growth since the 1970s, compared to low- and mid-income countries. The changes in VKT for places like Japan, the Netherlands, and South Korea primarily comes from retrofitting existing infrastructure to utilize land and street space more efficiently. In cities the Global South, however, where much infrastructure is still being planned, there is a different opportunity to prioritize sustainable transport.

Find more data on the state of sustainable transport around the world with ITDP’s Atlas.

Possibilities in the Global South

The urban forms of buildings and land use can take far longer to retrofit and inspire even more political resistance, as the amount of money required for change can be substantial, and the timeframe to reshape urban environments can be very long, especially in slower-growth markets. However, in cities still experiencing rapid growth, as with many regions in the Global South, a greater proportion of buildings and streets remain to be built as populations grow, and urban areas expand outward.

This presents a unique opportunity to proactively limit VKT in these regions by designing built environments that support walking, cycling, and public transport from the outset, rather than retrofitting later after unsustainable choices have already been made. With the right policies and design standards in place, entire neighborhoods and communities can be planned around accessible mobility, rather than around highways, parking, and private cars. While notable re-development efforts are also underway in car-oriented areas of the U.S. and Europe, these regions’ slow pace of investment and implementation limits the number and scale of such projects. In contrast, rapidly growing cities in low- and mid-income cities still have the chance to integrate sustainable mobility into their policies and designs when it is most urgent.

Watch this video to learn more about the compact cities and electrification ‘love story’.

One advantage for Global South cities is that they tend to have significantly higher population densities. For instance, compared to the global average of 19,900 people per km², Nairobi, Kenya has 39,400 ppkm², Addis Ababa, Ethiopia has 28,900, Chennai, India has 22,300, and Salvador, Brazil has 19,800 ppkm². Denser urban environments make walking, cycling, and public transit not only more viable and cost-effective, but often more convenient for short and medium-distance trips. In addition, because of the high costs of car ownership, vehicle use still remains relatively low in many places in the Global South, as evidenced by Kenya and Brazil’s VKT per capita being approximately 81% lower than that of the U.S. (2022). It stands to reason that cementing long-term urban plans and infrastructure policies for active mobility and public transit is more critical in these regions than ever.

If these governments can de-couple economic growth from the need for driving to access jobs or services, the scale of reduction in VKT could be significant. Countries with dense, rapidly developing urban centers are in a critical window to shape resident’s travel behaviors and to build public support for long-term, sustainable public transport operations. Fortunately, these policies also have the benefit of making cities cleaner, more equitable, quieter, and easier to navigate, while also creating jobs through public transit systems. They also save everyone a lot of money compared to owning and maintaining individual vehicles. In fast-growing, high-density cities, it is clear that it is more practical and cost-effective to choose walking, cycling, and transit now, rather than face the high challenges of retrofitting poor infrastructure later.

Strategic investments into sustainable mobility, rather than private vehicles, will help ensure that future urban growth supports climate goals, economic inclusion, and livability for us all.