September 19, 2024

Proving That Off-Street Parking Reform Can Lower Emissions and Housing Costs

In the struggle against climate change, it can feel that we are constantly being asked to sacrifice material desires.

A new ITDP data tool demonstrates how parking reforms can cut emissions and help build more housing in your city – access it here.

Most people do not want to take cold showers, pay more for electricity, or give up eating steak. It gets exhausting. There are a vast number of interventions that are good for both the economy and environment, and it is especially exciting to find something that will make it easier for us to afford accessible homes while also slashing emissions in the economy’s highest-emitting sector. That is why it is so exciting — as dry as it may sound — to reform the regulations of off-street parking.

But first, let us talk more about the problem. Most cities worldwide require that every new residential or commercial space be built with one or more parking spaces, regardless of whether occupants actually own cars. This policy is called a “parking minimum“, and you might expect that it will make things more convenient for people by ensuring parking is available at key destinations. But, in practice, it ensures that only parking is available at destinations and not space for much else. Parking minimums cause two big problems. First, it makes apartments more expensive. The price of apartments is determined by the cost of constructing the building, and parking garages can cost as much as $50,000 USD per spot to develop. That just gets added to the price of every apartment or housing unit.

Second, it is a subsidy for greenhouse gas emissions. If you had to choose to pay for a parking space, you might think twice before buying a car. You might think about using that money for other things, instead, like education or investments or even a vacation, and keep riding public transit for a while longer. But in most cities worldwide, you have already been forced to pay for the parking space as part of your cost of rent or a mortgage. In that case, many people may consider acquiring a car they may not necessarily need simply because of the available parking.

Given that an average passenger vehicle emits nearly 4.6 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide per year, that adds up to an astounding number of car-related emissions. In addition, with parking minimums, buildings must provide parking even if they are located in dense, walkable downtowns well-served by transit option. Parking availability incentivizes unnecessary and polluting driving trips, as well as related costs, even when other low-emission and affordable options may be readily available.

Continue reading about the importance of both on- and off-street parking reforms in this deep-dive report.

The movement to get rid of these “parking minimums” is picking up steam worldwide. Over 80 cities across North America have already gotten rid of them, even if just at the neighborhood-level. Other cities around the world are joining in and those without parking minimums are avoiding adopting them in the first place. It is easy to see why. Getting rid of a parking minimum lowers the cost of housing. Less expensive housing makes it easier for everyone to afford a home and makes it easier for people who already have a home to choose better ones. By removing the incentive for car-ownership, it also reduces massive amounts of greenhouse gas emissions at no cost to the taxpayer.

It is not a bad thing for people who want to drive, of course. However, the collective costs of urban space allocated to parking ultimately means there is no such thing as a ‘free’ parking spot when it is effectively incorporated into the cost of everyone’s housing. Removing minimums does not take away existing parking, it just should not require new parking be built so that the impacts are gradual and drivers will still have access to the parking that is already there. Until recently, the evidence for these benefits had mostly been anecdotal. You could walk around a city with new parking policies and perhaps see more green space rather than surface lots, but there was not a lot of data to prove the actual impact on costs or emissions.

Now, cutting-edge research from cities as diverse as San Francisco, USA; Mexico City, Mexico; and London, UK has given us a detailed understanding of the effects of eliminating or reducing parking minimums. For example, in Mexico City, policies to remove parking minimums that began in 2017 will result in the reduction of up to 17,000 cars on the city’s streets every year through 2030. In São Paulo, removing parking minimums near public transport stations enabled developers to build more social housing units closer to the city center. Drawing from these models, ITDP has integrated this knowledge into a user-friendly, free, and public tool that makes it possible for anyone to know what getting rid of parking minimums could do in their city.

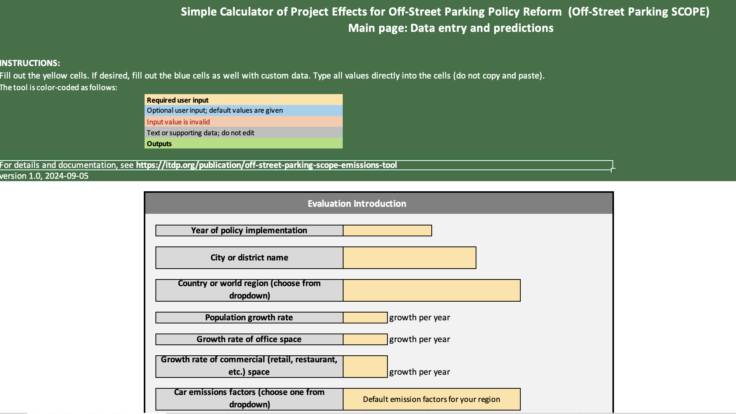

The Simple Calculator of Project Effects for Off-Street Parking Regulation (the Off-Street Parking SCOPE Tool) is an Excel tool that will tell you just how much your city stands to gain in terms of both reduced emissions and increased housing availability if it reforms its parking policies. The user-friendly spreadsheet helps users assess the potential climate and air quality impacts of off-street parking strategies by inputting certain parameters about their cities to generate estimated values. So, just how much does your city stand to gain? Let’s look at an example in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

In 2019, Rio became the first city in Brazil to pass parking legislation. About 16 million people lived in about 7.7 million households, according to Brazil’s census. Of those, about 4.8 million lived in a building that required at least 1 parking space per residence. Since that regulation was removed, we estimate that builders have started building about one parking space for every two units instead.

That means that Rio de Janeiro could build up to 1,020 apartments by 2029 to house its growing population,1,020 apartments that would not have been built under the old policy. It also means that up to 1.6 million fewer people will own cars, resulting in about 19,000 fewer tonnes of greenhouse gas emitted up to 2029. According to the EPA, that is as much as planting 314,000 trees. The Parking SCOPE model is ultimately meant to help planners, policymakers, funders, and advocates estimate the emissions impacts of policies for off-street parking reform.

The purpose of this parking tool and ITDP’s other SCOPE models (access the Bus Rapid Transit or BRT SCOPE here) goes beyond mere impact evaluation: they are designed to encourage high quality project design, support a holistic view of the connected parts of a city’s transport system, increase consistency, and maintain objectivity in planning.

Stay up to date on new releases, including a SCOPE model for sidewalks and footpaths, as well as a user-friendly web interface version of these tools.