September 09, 2024

This Indian City Proves Walkable Infrastructure Has Big Climate and Health Benefits

For most people living in cities, every journey or commute begins and ends with a walk.

Explore walkability data in your city with ITDP’s Atlas of Sustainable City Transport.

For residents in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where urban areas are often densely planned and populated, walking is sometimes the most affordable, easiest, and only accessible form of mobility. Yet, in so many cities around the world, well-designed, inclusive, and attractive sidewalks and footpaths are lacking to support pedestrians. The best mobility solutions can often be the simplest — particularly when it comes to harnessing as intuitive a form of movement as walking.

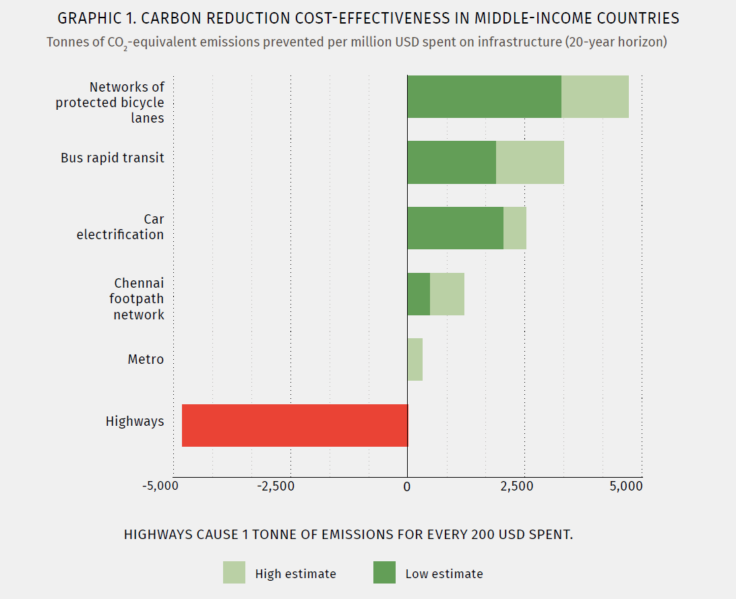

In a new report developed with ITDP India, Steps to Sustainability: The Impacts of New Footpaths Evaluation on Mode Choice in Chennai, strong evidence is presented from studies and years of data collection that demonstrate that improved footpaths and walking infrastructure is a highly cost-effective means to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), improve public health, save money for residents, and enhance public safety in LMIC cities. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate this connection empirically between urban footpaths and their related public benefits.

Between 2013 and 2019, the city of Chennai, India designed and built footpaths on more than 100 kilometers of streets. Using data collected in 2019, ITDP’s studies found that between 9% and 29% of people walking on the improved footpaths would have used a private motorized mode of travel if the footpaths had not been improved. As a result, the research estimates that between 4,200 tonnes and 12,000 tonnes of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gas emissions are prevented annually in Chennai thanks to the footpath improvements. This is equivalent to taking about 1,000 to 2,900 cars off the road for one year.

Additionally, by shifting away from motor vehicles, footpath users helped reduce air pollution and, with the increased walking activity, helped prevent about 340 deaths each year from noncommunicable diseases. By analyzing the impacts of Chennai’s footpath transformations completed over these six years, this research shows the significant potential for improving and expanding footpath networks across Indian cities with key evidence. It is clear that enhancing such infrastructure can have significant benefits for modal shift, the climate, air quality, and public health.

A before (left) and after (right) example of footpath improvements in Chennai.

Chennai has been transforming its streets over the past decade for the safety, comfort, and inclusivity of its residents. Previously, footpaths were largely nonexistent in the city except for a few locations with very poor-quality footpaths. In 2014, the city adopted the Non-Motorised Transport (NMT) Policy to dedicate 60% of its transport budget towards NMT work. Chennai was the first Indian city to adopt a policy of this kind and, with the support of ITDP, it has since:

- Transformed over 100 kilometers of the city’s streets for more accessible and equitable mobility, while also improving nearly 300 bus stops and 60 school zones;

- Inaugurated the Pondy Bazaar Pedestrian Plaza as a model for people-friendly public spaces;

- Scaled-up street transformations across six city neighborhoods;

- Built the capacity of municipal engineers through study tours, workshops, and formal training programs;

- Adopted Complete Street Guidelines to inform all future street design projects; and

- Engaged the public in a participatory planning process through tactical urbanism initiatives and stakeholder consultations.

Watch ITDP’s The Power of Walkability webinar to learn more.

Based on user intercept surveys, the research ultimately found that many of Chennai’s pedestrians chose to shift their trips to walking as a result of the new infrastructure. In addition to the emissions reductions and air quality improvements, investments in footpaths could also lead to economic savings for the city by helping reduce more tonnes of GHGs per INR crore spent than other infrastructure projects, particularly metro rail. Additionally, 95% of survey respondents reported feeling safer on the improved streets. Clearly, investments in walking infrastructure have significant and tangible benefits in lower- or middle-income countries. These benefits accrue not only for pedestrians but for society at large and, even the example set by one city like Chennai, can certainly have implications for many others.

From these findings, it is clear that well-designed footpaths are an efficient way to shift city residents away from polluting vehicles, reduce thousands of tonnes of GHGs per year, and improve overall well-being. Now, we need more cities to take similar steps forward.