July 06, 2022

Cycling’s Gender Gap: Breaking The Cycle of Inequality

This piece was authored by ITDP’s Chief Knowledge Officer Aimee Gauthier.

Cycling acts as a mirror to societal inequities — in who has access, who feels safe on the street, and whose trips are being planned for.

In a township outside of Cape Town, South Africa, a community health care provider named Rosie received a bicycle for the first time. In an interview with ITDP, she mentioned that this was the first time she had ever owned a bicycle — typically in her community, if a bike entered the household, it went to the boys or men first. This time however, this bicycle was hers alone — and it would make a significant difference for her work traveling between households and neighborhoods to see patients. Not only could she serve more people in less time than before, the bicycle serves as an important symbol of independence. For Rosie and many women like her around the world, cycling holds a key to both mobility and freedom.

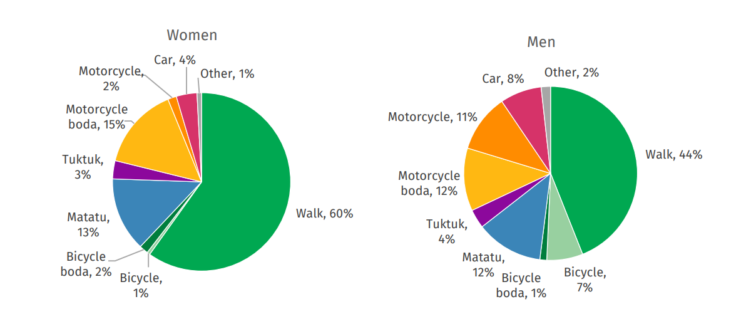

A critical gender gap exists in cycling — in fact, it is one of the most stark illustrations of gender inequity amongst modes of transportation, and this dynamic persists in city after city. In Kisumu, Kenya, men account for 96% of all cyclists and use cycling for 7% of their trips — in contrast, women in Kisumu cycle for only 1% of theirs. This alarming ratio can also be found in a major cities like Rio de Janeiro, Brasil as well. When ITDP Brasil conducted mode share counts in downtown Rio de Janeiro, women ranged between 2.4% and 10.9% of all cyclists, with men ranging between 89% to 97.6%. It is important to note though that the one outlier that had a higher share for women (at 26.1%) was a location with protected cycle infrastructure. Even then, the imbalance between men and women remained very significant. Another example — in Delhi, India where 21% of trips are made on bicycles, women constituted only 2% of those riders.

These great disparities are not a reflection of gender preferences, but instead are an indication of persistent gender inequality. Cycling acts as a mirror to societal inequities — in who has access to bicycles, who feels comfortable and safe on streets, and whose trips are being planned for in our cities’ transport systems. But cycling can also offer a tremendous opportunity to increase access for women in cities and to empower them through mobility, as it did in the case of Rosie in South Africa.

Challenges to Gender Equality in Cycling

Several systemic issues contribute to these inequalities in cycling. First, many women and girls may not have consistent access to cycles and, as a result, may not have learned to ride them safely and effectively. In many places, women also do not have access to essential assets (including vehicles like cars and bicycles) as they tend to belong primarily to men. This limits the ability of women and girls to reach school, perform household duties, ride to or with friends, and reach places of employment. As some women assume child care duties, they may also feel less secure about cycling, with or without a child. Many times, cycles that can accommodate children may be expensive and hard to find, and often streets do not support safe and easy cycling.

Road safety concerns also heavily influence a woman’s decision to cycle. Many cities lack protected bike lanes and, even when they do have them, they are often not part of a connected network. We know that protected bike lanes are one of the best ways to encourage cycling for the risk-averse. As mentioned in the Rio de Janeiro example, dedicated and protected bike lanes are associated with encouraging a higher percentage of women to cycle. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the gender gap is still high in the Rio case, and additional barriers arise from societal constructs of gender; lack of access to bicycles to encourage more experience and confidence; and cultural perceptions that women should not cycle.

Furthermore, we know that marginalized women face even greater hardships when it comes to access. When exploring gender inequality, an intersectional approach — based on the concept developed by civil rights advocate and legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw — is needed. When it comes to gender and cycling, we need to account not only for people of all genders — including people who are non-binary or transgender — but also for a multiplicity of intersecting identities such as race, ethnicity, ability, income, age, and religion. All of these identities impact a person’s access to various transport modes and how safe and comfortable they feel using them.

Tying these challenges together, one of the biggest barriers for women moving through public space is the potential for urban violence. Women’s sense of personal security is often threatened by harassment and violence. When ITDP Brasil held focus groups with low-income women in the city of Recife, as detailed in the report Women’s and Children’s Access to the City, they found that cycling was the only topic that positively engaged women. This is due in part to the amount of harassment and gender violence they face while walking and using public transport. Even as they were concerned about road safety while cycling, the women interviewed saw the bike as a good mode for short trips that would save on transport costs, allow them to travel faster, and free them from waiting for the bus and the harassment experienced on public transport. Cycling can be viewed as a way to help women break out of the cycle of gender violence experienced in the public sphere, and as a chance to relieve women from negative public transport experiences.

Harnessing the Power of Cycling

The crisis of violence against women is a global phenomena that can’t be solved by cycling alone, but cycling can offer an important solution to helping women avoid harassment. It is important to note that in some cultures, however, women are not even encouraged or allowed to cycle in public and can be harassed just for doing so. As Kate Jelly writes in the Guardian, “[c]ycling does not eliminate the risk of harassment or violence for women, but it at least gives more personal control over route, speed, and time of travel and removes some of the vulnerability that comes with walking or being trapped in a dangerous situation on public transport or in a taxi.” Despite these systemic challenges, we know that cycling has the potential for dramatically increasing access for women, as well as giving them more independence and some freedom from harassment.

Women often travel differently than men due to societal roles and responsibilities, in part because of their caregiving and domestic duties (and most caregivers still are women). Because of these responsibilities, women tend to need to “trip chain”, wherein they take more complex, multi-modal trips and combine multiple stops in one journey in order to complete a range of activities. Cycling could allow them to more easily and quickly complete caregiving tasks, as well as carry more — whether it be children or goods. Cycling can also be good for babies and toddlers cycling with the caregiver, helping their socio-emotional and cognitive development. Cycling together allows for interaction, connection, and engagement between the child and both the caregiver and the environment.

A bicycle can be an immensely useful tool for time-constrained women to reach their destinations faster, and allow for a better and more cost-effective option for trip chaining. Cycling also offers a transport mode more likely to build community connections and provide more opportunities to engage with the local environment, for women and for those they cycle with. It is a solution that can bring together climate, health, and resilience and — if done through a gender lens — can do so in an empowering and equitable manner. Most of all, cycling allows women and girls to have freedom of movement, rather than being dependent on money, a parent, a husband, or an unreliable public transport service which can put them in danger or lead them to not travel at all (Dr. Kalpana Viswanath of Safetipin calls this concept forced immobility.) As one woman cyclist in Mexico City noted in interview with ITDP, there is nothing better than the freedom she gets from riding her bike — and the happiness, too.

Navigating A Path Forward

There are easy ways to increase access and encourage more women to cycle. First, it is critical for cities to build a connected and protected cycle network with lanes wide enough to accommodate slower riders, riders using cargo bikes or tricycles, or riders traveling as a family. Often when cycle lanes are built in a city, they are tied to big infrastructure projects like a BRT system or along a major commuter corridor. This neglects the development of a connected local network and fails to recognize the shorter types of trips that women may make in the neighborhood for caregiving activities, or in peripheral areas where low-income women may not have access to formal mass public transport. We need to invest in creating cycling cities that are more than just unconnected corridors along major commercial arterials.

Second, we need to actually increase access to bikes among women. Ideally, girls will have the same access and encouragement to ride at a young age as boys often do, but special programming may be needed in lieu of that. This can be done through bike giveaways, earn-a-bike programs, or through bikeshare systems. Cycle-only clubs for women and girls or dedicated cycle-to-school programs can also be helpful. For example in India, the “Power to Pedal” campaign led by Greenpeace has distributed hundreds of bicycles to women laborers from Delhi’s Zamrudpur community and Bangalore’s Munnade and Laggere garment labor unions, which was supplemented with skills training. Also in India, cities participating in the Freedom2Walk&Cycle national challenge program hosted over 40 cycling training camps to teach women and girls how to cycle. ITDP itself has given out bicycles to health care workers to help them better access their jobs, like in the South Africa example.

Bikeshare programs have also emerged as a way to give access to bikes for women who historically may not have had it. Ecobici, Mexico City’s bikeshare system, has almost twice the amount of women cyclists than the broader cycling mode share. Women were 40% of Ecobici’s riders, while the overall cycling mode share for women was 22%. It is important to note that access to bikeshare is not enough to overcome the prevailing gender gap. In Guadalajara, the city implemented a pilot project where low-income women were given a subsidized fare for public transport that included free access to the bikeshare system, although only 12% of local women have taken advantage of that program.

Fundamentally, we need to look at the broader social attitudes and cultural norms that reinforce the roles and behaviors of women and girls in society when it comes to cycling and transportation. BYCS, an international nonprofit that advocates for cycling, concluded in their Strengthening the Human Infrastructure of Cycling report that cities also need to look at soft measures that address barriers that come from perceptions, access to bicycles, ability to ride, and awareness. These can include: more open streets, awareness campaigns, cycle buses and school streets, earn-a-bike programs, cycle training, e-bike subsidy programs, and more.

Cities need to start ensuring that they are collecting disaggregated data about women and their travel behaviors, engaging with women to understand the barriers and challenges they face, and implementing programs to encourage cycling. Having women be part of the planning process and as decisionmakers can also help address this gap. Infrastructure and street design is an important component of encouraging women to cycle, as Marina Moscoso of Despacio noted in ITDP’s Twitter Space that was held on World Bicycle Day. This includes having slower traffic, good lighting, protected bike lanes, protected and safe intersections, and cycle infrastructure beyond just the main streets.

Some governments and cities are already beginning to center gender equity in their transport approaches. Ethiopia has released an ambitious non-motorized transport strategy that seeks to increase investment in walking and cycling in cities across the country. Addis Ababa, the capital city, is looking to build 200 kilometers of protected bike lanes by 2028, on its way to reaching a target of gender parity in cycling mode share. During the Q&A of the MOBILIZE Deep Dive Virtual Event held in December 2021, Ethiopia’s Minister of Transport Dagmawit Moges Bekele reflected on this goal, saying her dream is to see young girls cycling to school because “…I did not get that opportunity when I was young, but I believe this young generation, girls and boys, deserve to have better access.”

If we do not close the gender gap in cycling, then we will certainly not be successful in meeting our climate needs either. As Minister Bekele noted during the MOBILIZE event, women and girls deserve to have healthier, safer, and better access to their environments, and fostering cycling-centric cities can create a pathway for achieving just that. To address many urgent equity and environmental issues, ITDP launched its Cycling Cities campaign, which seeks to create global cities of access and independence in a way that responds to climate change while envisioning better cities for us all.

Ultimately, as researchers Lea Ravensbergen, Ron Buliung, and Nicole Laliberte argue, we need to ensure that while we make it easier for women to cycle, we also recognize and understand why cycling reflects such an enormous gender gap. This requires considering the underlying social, political, economic, and historical reasons that have driven such prevalent differences. We need to integrate both the mobility patterns of difference, and the ways in which gender affects those mobility and travel behaviors. The extreme gender gap in transport that we see in so many cities illuminates gender inequality as a whole in our society. To solve for them, we need to take a systemic and intersectional approach that, as a start, addresses the legacies of gender violence and discrimination that impact women around the world.

View and share ITDP’s animation on gender and cycling created for World Bicycle Day 2022 (below) and listen to ITDP’s Twitter Space conversation on the topic.