October 03, 2025

How to Keep SUVs Out of Emerging Economies

This article was originally published in the Vision Zero Cities Journal, released by our partners at Transportation Alternatives as part of the annual 2025 Vision Zero Cities conference.

By Dana Yanocha, ITDP Global

Car-centric transportation systems have seriously damaged the environment, safety, and livability of cities around the world. Fossil-fuel-based passenger transport is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, and the impacts of climate change are already wreaking havoc on our planet’s ecosystems and economies. As low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) increasingly urbanize and grow their economies, they could follow the dangerous path of many wealthy nations in establishing car-dominated transport systems and see similar negative outcomes. Alternatively, LMICs can forge a different path — one that prioritizes safe infrastructure for walking, cycling, and public transportation, keeps vehicle kilometers traveled to a minimum, and limits the size of personal vehicles.

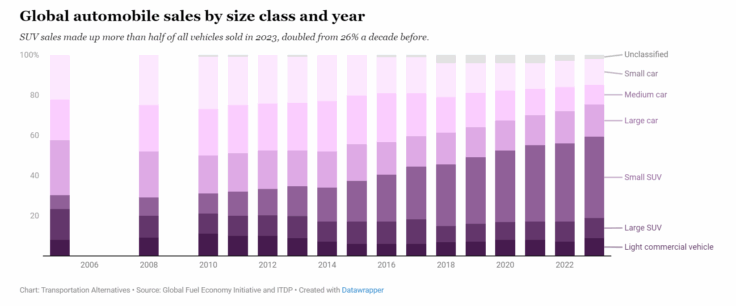

Over the past two decades, cars have gotten larger, exacerbating pollution and road safety issues. SUVs are the second-largest contributor to the global increase in CO2 emissions since 2010, behind the power sector but ahead of heavy industry. As of 2022, half of the new vehicles sold globally are SUVs, up from one in five in 2010. This is not only the case in developed countries like the U.S. and China — SUV sales have also increased in India, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, and other emerging economies. And they are continuing to rise: in Mexico, for example, SUVs are on track to represent more than 80% of new vehicles by 2050.

Large vehicles like SUVs also contribute to high crash and fatality rates, especially for people walking and riding bicycles. This is a major concern, especially in countries where the majority of trips are made on foot or bicycle, but where rapid urbanization (and motorization) is occurring. As LMICs continue to grow their economies, vehicle ownership — and SUV ownership in particular — will likely increase unless policies are implemented to prioritize sustainable modes. Cities in these regions have a critical opportunity to avoid the pitfalls of car-centric development, including more lethal crash outcomes, high road construction and maintenance costs, pollution, and inequitable mobility, that are ingrained in countries like the United States.

Impacts of Vehicle Size and Use on Road Safety

Both vehicles’ size and prevalence on our streets have significant implications for road safety, particularly for pedestrians and people on bicycles. Reducing vehicle size and use has the potential to reduce road fatalities significantly. In modeling by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, both reducing the size of vehicles and encouraging mode shift to sustainable transport by 2050 have the greatest potential to improve road safety in wealthy nations and LMICs.

In India, nearly 183,000 fatal crashes in urban areas are projected annually by 2050 if current vehicle trends continue. Implementing vehicle size policies alone would reduce fatal urban crashes by about 10% annually, but adopting those policies alongside mode shift to sustainable transport brings the total projected fatal urban crashes down to 93,000 — a 51% reduction from the business-as-usual baseline. Additional improvements to infrastructure or vehicle design have the potential to further improve street safety.

Similarly, reducing vehicle sizes in Mexican cities would result in a 7% annual decrease in fatal crashes, and more than one-third fewer fatal crashes per year through a combination of reducing vehicle size and increasing use of sustainable modes. In all countries, people on foot and bikes stand to see the greatest safety improvements. Reducing vehicle size and use reduces fatal crashes between cars and people walking and biking by about half compared to the business-as-usual baseline. In India’s case, vehicle crashes with pedestrians or people on bicycles are projected to fall about 60% from 51,000 per year in the baseline scenario to 21,000 per year if vehicle sizes and use can be reduced. In Brazil, similar improvements could lower the baseline of about 9,000 vehicle-pedestrian/bicycle crashes to about 4,400.

Recommendations for National and City Governments

These findings can directly inform how local and national governments approach road safety broadly, and design and implement Vision Zero actions in particular. Actions to reduce vehicle use are widely known, and many LMIC cities are already working towards them: parking pricing, congestion pricing, vehicle access restrictions, and road space reallocation on the “push” side, and improving sustainable transport service and affordability on the “pull” side.

Indeed, car ownership and use are still relatively low in most LMIC cities, and implementing these measures will help to keep it that way. However, national and local governments should actively ensure that the (hopefully small number of) trips made by car are made in as small and safe a car as possible. While catalyzing a shift to public transport, walking, and cycling has been a cornerstone of many road safety policies, a complementary focus on limiting vehicle size will further reduce road fatalities.

At the national level, large countries with auto industries should adopt vehicle fuel economy or greenhouse gas emission standards (or revise existing standards) that do not incentivize the production of larger vehicles. In the United States and the European Union, larger, heavier vehicles are held to more lenient fuel economy or emissions standards, which has incentivized their production over smaller, lighter vehicles.

Countries with limited domestic auto manufacturing might consider trade policies such as tariffs or quotas that limit the importation of large vehicles. For example, countries could raise value-added taxes (VAT) or import taxes on passenger vehicles over a certain weight, similar to higher VAT rates placed on luxury goods. The US has had a “gas guzzler tax” for decades that is paid by manufacturers or importers for some vehicles (ironically, and cripplingly, it excludes SUVs and pickup trucks) that fall below a certain fuel economy threshold — something similar could be adopted for passenger vehicles over a certain size or weight. Import quotas on large passenger vehicles could also limit their supply and raise prices relative to smaller vehicles.

On a more local level, cities can more explicitly acknowledge the impact of larger vehicles on road safety in their Vision Zero action plans. As part of the Safe System Approach, advocates and policymakers should focus on reducing vehicle size alongside long-standing priorities like reducing vehicle speeds. This means committing to policies that disincentivize large light-duty vehicles. One lever that cities can use to disincentivize large vehicles is to scale parking fees by vehicle size or weight.

Beyond the well-published weight-based parking permits in Montreal and Paris, tying vehicle size to parking fees is also gaining traction outside of the Global North. An area-level parking policy for the Chennai Metro Area was recently passed and specifically notes vehicle size as a key variable that will influence on-street parking fees. Similarly, Kigali, Rwanda’s parking policy will link vehicle size to on-street parking fees as part of its demand-based priced program.

Read the latest articles in the Vision Zero Cities Journal.

Another less common approach is linking vehicle registration fees to vehicle weight, as is the case in Washington, DC, where heavy vehicles cost about twice as much to register ($155) as lighter vehicles ($72). While Washington, DC, is currently the only city with this type of policy in place, the administrative burden is relatively low and could be interesting for low-capacity governments to pursue, even if just as a signal.

When implemented together, policies that encourage more walking, cycling, and public transport and limit vehicle size have the greatest potential to reduce fatal traffic crashes. Cities and countries with large shares of trips made by pedestrians and cyclists, common in low- and middle-income countries where car ownership is out of reach of many, will see the largest impacts of these coordinated policies.

Combating global vehicle size growth and the likelihood of vehicle use to surge in increasingly motorized nations is a critical step toward achieving Vision Zero. Cities and national governments should work in parallel to achieve these complementary goals.