March 22, 2021

The Next Pandemic Surge: Traffic

2021. This year has begun with more uncertainty than 2020. Many questions remain: about the vaccine, government readiness, what the future may hold, and when things might change.

Among the many existential challenges facing the world this year, traffic looms as a seldom discussed time bomb. During the pandemic, cities largely stood still. Streets emptied, with only essential movement: lockdowns and fear of the unknown dominated discussions. Now with vaccine access expanding, along with better knowledge about how to slow the spread of the disease, there is reason to hope and see a possible path forward.

Still we do not know what the new world will look like, or more importantly, if the way we travel will be the same again. Across the globe, from China to Europe to the US, car traffic is trending upwards, and in some cases, above where it was before the pandemic. Greenhouse gas emissions are increasing, the brief improvement in air quality and drop in emissions last spring, has dissipated. For people with means, driving feels like a safe transportation option – a way to maintain social distancing and reduce contact with crowds – which has led to an increase in vehicle purchases in some wealthy countries last year. However, vehicle purchases dropped significantly and have not recovered to pre-pandemic levels in Latin America, Indonesia, and other less car-dependent countries.

But as travel, work, and life begin to return to normal, cities without a strategy to de-prioritize the use of private vehicles run the risk of defaulting to past, car-centered, mistakes.

In 2020, even though driving was generally down, traffic related deaths rose by 8% in the United States while traffic related deaths remain high throughout the world. 1.35 million people die every year from car crashes, many of these because the roads they are traveling on are designed to move cars as quickly as possible without accommodating other road users like pedestrians or cyclists. This problem is only going to get worse if changes aren’t made to build and restructure roads for pedestrians and cycling.

The pandemic forced many cities to re-evaluate their business-as-usual, car-centric systems, providing an opportunity to pause and think about what systems work and which might not. What became clear was how quickly people took to enjoying the outdoors when cars were absent. Many streets became open streets and gave people of all ages and abilities the opportunity to walk, cycle, and enjoy public green spaces. But as travel, work, and life begin to return to normal, cities without a strategy to de-prioritize the use of private vehicles run the risk of defaulting to past, car-centered, mistakes. The possibility of a true carmageddon is upon us and cities need to act now to ensure we don’t go back to (or, in cities with low vehicle use, start to see) hours-long traffic jams – or that traffic becomes much worse with more cars on the road.

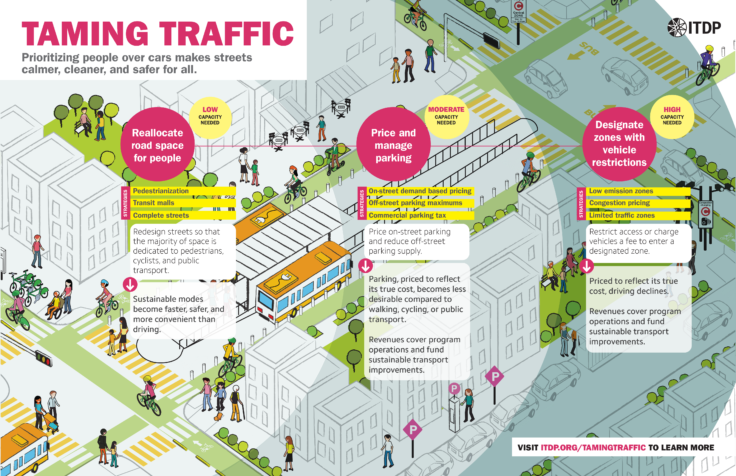

ITDP’s Taming Traffic paper outlines tools, large and small, that cities can use to reduce car use equitably and sustainably in the post-pandemic world.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach, but starting with small, even temporary interventions that repurpose road space for walking, cycling, and transit, and then scaling up to more complex policies like parking pricing and congestion pricing over time is a realistic path for many cities. Rebuilding with this human scale in mind will give cities an opportunity to move away from the default of car-centric planning and commit to actions that will mitigate the existential threat of climate change, and bring about more livable urban spaces.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach, but starting with small, even temporary interventions that repurpose road space for walking, cycling, and transit, and then scaling up to more complex policies like parking pricing and congestion pricing over time is a realistic path for many cities. Rebuilding with this human scale in mind will give cities an opportunity to move away from the default of car-centric planning and commit to actions that will mitigate the existential threat of climate change, and bring about more livable urban spaces.

Induced Demand: More Roads means More Traffic

Time and again the proposed solution to traffic is to build more roads. This assumption, based on physics, seems intuitive. Too many cars need more space to move, and by creating more roads, or adding more lanes, the cars will spread out and traffic will decrease. However, this rarely happens. Instead, when more roads are built or lanes are expanded, traffic may temporarily ease, until it eventually gets worse than before. The theory of induced demand is well known to sustainable transportation advocates but might be new for others. The theory posits that more roads breed more drivers, so when a road is built or expanded to alleviate congestion, it actually has the opposite effect. More roads give people a perception of more opportunities to drive to their destination more quickly, so they purchase more cars and move farther from their workplace. All of these are done under the assumption that their travel time will not increase, but this is never the case because in this scenario, freight and people have to travel farther, so eventually traffic returns to previous levels. Cities that have invested in “traffic easing” highway expansion projects to the tune of billions of dollars end up with the same, if not more, congestion after these boondoggles are completed. When traffic picks up post-pandemic, cities cannot fall back on disproven policies like widening highways. Instead, cities must think differently: reduce traffic by prioritizing people and public space over vehicles.

Way Forward

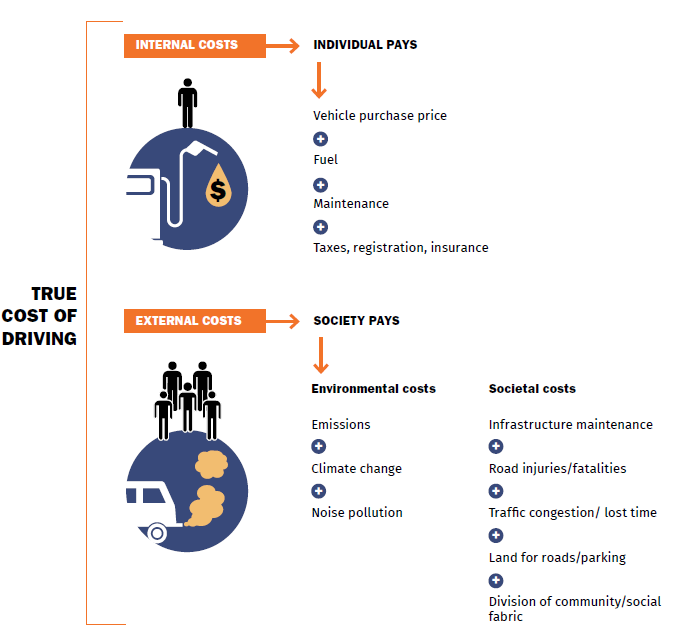

What is clear is that the status quo is unlivable, inequitable, and dangerous for the planet. The external costs of driving have disproportionately affected vulnerable groups including the poor, older adults, children, and people with disabilities, regardless of vehicle usage. This history of underpricing road use will continue to fuel a dependence on vehicles, resulting in congestion, pollution, and sprawl. We know that a world with more cars will mean more road deaths, more hours behind the wheel, more greenhouse gas emissions, longer commutes, and lower quality of life.

To rebuild, cities must curb the use of private vehicles and prioritize high-quality infrastructure that makes walking, cycling, and public transport a safe, attractive, and efficient alternative to driving. It is not too late to act but now is the moment.

Read Taming Traffic here.