March 07, 2025

Reforming Parking Doesn’t Require Cities to Reinvent the Wheel

A version of this article was originally published in the No. 36 issue of the Sustainable Transport Magazine.

By Jacob Mason and Dana Yanocha (ITDP Global)

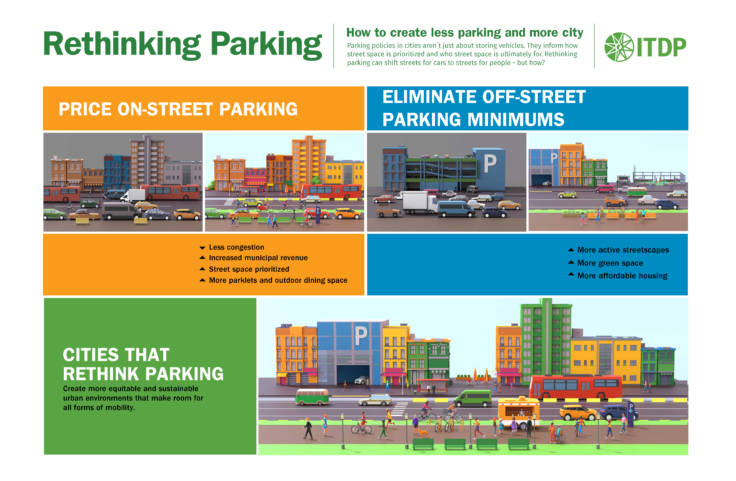

In the city of Guadalajara, Mexico, sustainable mobility is making strides. The city has been implementing more shared bikes, safer bike lanes, and improved pedestrian pathways alongside a new bus rapid transit (BRT) line. But another key component of the area’s transformation is lesser known: better parking management. Our streets are critical for facilitating walking, cycling, and public transport, in addition to private vehicles. But in too many cities, parking has become the primary use of most street space. Unlike other aspects of transport, which require government infrastructure and support, parking often flourishes in the absence of public intervention. Parked cars are overtaking curb space, bike lanes, crosswalks, and footpaths, making it harder and less safe for everyone to move around. In many cities, a lack of clear rules, education, and enforcement leads to parking behaviors that are making our streets hostile for everyone. It is time to rethink our cities’ relationship with parking.

Where Parking Policy Falls Behind

Even when parking is addressed, governments often focus on reacting to undesirable behavior, like double parking or crowding at intersections. In other circumstances, parking is treated purely as a revenue source to offset taxes. Too often, parking policies are implemented with little connection to broader policy goals, such as improving transit access or reducing air pollution, or even as part of a larger vision for urban transport. Many cities, for example, might just install parking meters in busy areas to raise revenues, but fail to consider how the funds can benefit other transit modes. A more thoughtful approach to on-street parking policy is foundational to supporting comprehensive, equitable mobility in any city.

Improvements to street-side parking and curb management can help keep sidewalks and cycle paths clear, for instance, making walking, cycling, and transit stops easier to access. Charging the market rates for on-street parking can also make the true cost of each car trip more explicit, helping make other modes more attractive by comparison. The revenue gained from better management can, in turn, fund investments into infrastructure for pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders. When it comes to off-street parking and garages, cities that reduce or eliminate requirements for parking enable developers to instead build more housing units per building, potentially reducing the cost of rent and housing prices. This also makes it less expensive to live in more walkable areas.

Reinventing Parking, From Mexico to Indonesia

Growing evidence from ITDP’s own work as a leading advocate for parking reform has made it clear that the provision of expansive, low-cost parking is bad for both the climate and urban mobility. Our teams have seen that policies to better regulate parking can and have proven successful in diverse cities. This may be attributed to new parking policies being relatively easy to implement on a pilot scale before being expanded. Because they can be implemented in smaller areas first, they are easier to tailor to local conditions and community feedback via different rules and pricing. For example, if parking spaces on a block need to be removed, parking costs on nearby streets can be increased to manage extra demand.

In cities in Mexico and Indonesia, ITDP has been collaborating with local governments and advocates to offer expertise and capacity in order to advance parking reforms. Fortunately, many urban policymakers are starting to understand the positive impacts of change and the need to reclaim street space, generate public revenue, and reduce the overall demand for driving. Many cities are also beginning to take the view that improving pricing and management is a critical piece of long- term transport and development planning.

For example, Guadalajara’s municipal government initiated a series of reforms over the last few years to prioritize walking, cycling, and transit by restructuring parking and driving policies. A major aspect of this involved the expansion of regulated parking zones in the city’s busy center. These zones feature variable pricing structures where parking fees are higher at peak hours. This approach discourages long-term parking in high-demand areas, ensuring that spaces are available for short-term users and incentivizing alternative mobility options. The revenue generated from this is subsequently earmarked for reinvestment in public transit and related infrastructure projects.

This helps to create a direct link between better parking management and the city’s investment in sustainable transport, allowing Guadalajara to improve its overall public services while simultaneously reducing the need for private vehicle trips. In tandem with these reforms, Guadalajara has also focused on improving the reach of its cycling and pedestrian networks to provide more integrated mobility networks. Notably, the city has expanded its Mibici bikeshare program to serve more residents and tourists alongside upgrades to cycle lanes. Across the world, in Jakarta, Indonesia, ITDP Indonesia has been working with the local government since 2017 to reshape their parking regulations. Amidst land scarcity, high congestion, and rising property costs citywide, ITDP Indonesia research found that, as of 2021, the 30,000 parking spaces in Jakarta’s main districts amount to an astounding 265,000 m² of land.

To begin reclaiming this usable space from private vehicles, the government has adopted a technologically driven approach to parking management. One key initiative includes the use of smart parking systems that leverage mobile apps to help drivers locate available parking spaces in real time. By minimizing the time spent searching for parking, this can help reduce congestion, improve traffic flow, and assist drivers in making better decisions. These efforts also incorporate dynamic pricing, where parking fees vary based on demand.

Jakarta has also been working to reduce minimum parking requirements for new building developments as part of a low emission zone (LEZ) pilot in central areas. New provisions integrated into the city’s building codes recommend that percentages of building space previously allocated to parking should be shifted to parks, affordable housing, commercial areas, or other uses. In addition, as part of the LEZ, the new provisions require the amount of bicycle parking at buildings to be at least 10% of the total vehicle capacity to encourage more people to cycle. Collectively, these actions show promising momentum in one of the world’s most congested cities, helping Jakarta become a model for reform.

The changes underway in Guadalajara and Jakarta are just a few examples of how rethinking parking can help policymakers and everyday people reshape our understanding of urban space and mobility. By reducing demand and reliance on private vehicle trips, these efforts demonstrate that cities do not need to employ drastic actions to shift behaviors and make walking, cycling, and public transit more accessible. Rather, by adjusting existing systems, removing outdated regulations, and leveraging new technologies, cities can influence when and if people decide to drive. It is no longer logical to continue building low-cost or free parking that puts a physical, financial, and environmental burden on everyone, especially when so many cities face crises of housing, climate, and equity.

An equitable future for cities begins by rethinking our relationship with our vehicles and streets.